Archives

Furthermore prior studies only examined habit formation for

Furthermore, prior studies only examined habit formation for food reinforcers, but responding for ethanol becomes habitual more rapidly than responding for food (Dickinson et al., 2002; Corbit et al., 2012). Thus, adolescents may form ethanol-seeking habits at a different rate than food seeking habit. Indeed, previous research has demonstrated that food habits form more quickly in females than in males, but that the opposite is true for ethanol habit formation (Quinn et al., 2007; Barker et al., 2010). Therefore, in the present study we compared the rate of habit formation for an ethanol reinforcer in adolescent and adult rats using the contingency degradation paradigm. We also compa red later adult ethanol self-administration in rats with adolescent vs. adult onset ethanol exposure.

red later adult ethanol self-administration in rats with adolescent vs. adult onset ethanol exposure.

Materials and methods

Results

Groups of 12 adolescents and 12 adults began training. 5 adolescents and 4 adults acquired self-administration within 5 days, while an additional 5 adolescents and 4 adults acquired after 5 additional days of FR1 training. The smaller groups were each analyzed separately as the age range  differed slightly for testing, but we observed the same results in both subgroups, so the data were combined and all analyses represent results from a group of 10 adolescents and 8 adults. The ages of the 2 subgroups at each stage of testing are shown in Fig. 1A. Six of the rats (2 adolescents and 4 adults) never acquired self-administration to our criteria (earning at least 10 reinforcers on FR1) and were not analyzed further. The number of rats failing to acquire is within the range often observed in rat self-administration studies in our laboratory.

differed slightly for testing, but we observed the same results in both subgroups, so the data were combined and all analyses represent results from a group of 10 adolescents and 8 adults. The ages of the 2 subgroups at each stage of testing are shown in Fig. 1A. Six of the rats (2 adolescents and 4 adults) never acquired self-administration to our criteria (earning at least 10 reinforcers on FR1) and were not analyzed further. The number of rats failing to acquire is within the range often observed in rat self-administration studies in our laboratory.

Discussion

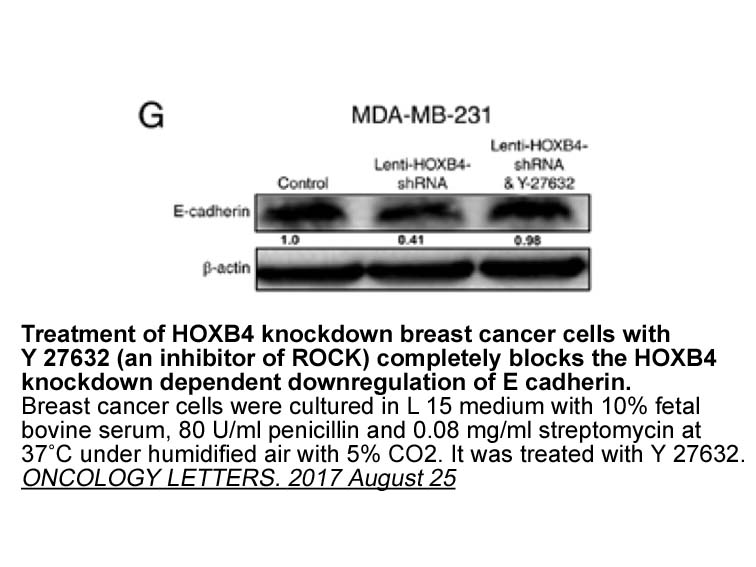

Despite the fact that adults formed ethanol-seeking habits more readily than adolescents, adolescents consistently consumed higher doses of ethanol than adults. Moreover, when the rats that began ethanol self-administration in adolescence were abstained from ethanol until they rho kinase inhibitors reached adulthood (PND70), and were reassessed on their levels of ethanol self-administration, the adolescent onset drinkers consumed significantly more ethanol than the adult onset drinkers. Therefore, adolescents do demonstrate a greater propensity to respond for ethanol reinforcement than adults, as has been reported previously (Helms et al., 2014; Vetter et al., 2007; Doremus et al., 2005), and this ethanol seeking and consumption appears to be goal-directed rather than habitual. However, Polyploid is possible that the increased adult intake was due to adolescent exposure to a sweetened ethanol solution, which has been shown to promote acceptance of that solution in adulthood (Broadwater et al., 2013). Nevertheless, in the present experiment both adolescent and adult onset groups had prior exposure to the solution, suggesting that acceptance levels should have been similar, and that the increased self-administration in the adolescent onset group is at least partially due to greater motivation for the solution. Indeed, other studies have found that injections of ethanol in early adolescence increased ethanol drinking and operant self-administration in adulthood (Alaux-Cantin et al., 2013), and that monkeys that begin drinking in adolescence go on to consume more ethanol in adulthood (Helms et al., 2014). However, it should be noted that one study has found that adolescent home cage, unlimited access to ethanol in a two-bottle choice paradigm does not significantly increase later adult drinking (Vetter et al., 2007). The difference between the Vetter et al., study and the other studies could be the difference in limited versus unlimited access paradigms, which results in a large difference in the total amount of ethanol consumed, or to other adaptations induced by different access conditions.

Nevertheless, our results suggest that adolescent onset ethanol exposure results in neural plasticity or pharmacological adaptations that either maintains enhanced motivation for ethanol, reduces the aversive qualities of ethanol, or alters the pharmacokinetic properties of alcohol in adulthood. Regardless of the mechanism, in this scenario, individuals that begin drinking ethanol in early adolescence are predicted to consume more ethanol in adulthood, and this high level of consumption could then become problematic due to habit formation. Early onset drinking may also make the formation of habits in adulthood more likely, as adolescent ethanol exposure can promote inflexible behavior in adulthood (Gass et al., 2014).